Politics

U.S. government debt is back in the spotlight.

A couple of forces have thrust the perennial issue back into public consciousness: the tax-cutting One Big Beautiful Bill Act and the U.S. credit-rating downgrade by Moody’s in May. Many deficit hawks are sounding the alarm on the sheer amount of money the federal government owes.

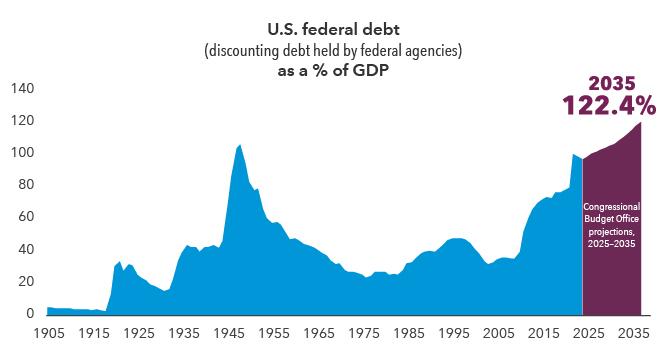

As of March 31, federal debt comprised between 97% and 120% of the nation's GDP, depending on whether you count federal debt such as Treasuries held by some part of the U.S. government. (GDP, or gross domestic product, is the total amount of economic activity that takes place in a nation or region every year.) Projections of the debt-to-GDP ratio generally point to a further rise.

Yet for all the hand-wringing around debt sustainability and annual deficits, there seems to be remarkably little concern in the markets. 10-year Treasury yields have fallen about a third of a point since the start of the year. The S&P 500 has also risen solidly for the year after dipping in April amid heavy tariff announcements.

So what does this all mean for an investor?

“I think a lot of investors probably don’t think about it,” says Darrell Spence, a Capital Group economist. “The downgrade suggests, at the margin, there’s a slightly, slightly smaller chance that Treasury holders won’t get paid back, but I’d consider concerns about that unwarranted at this stage.”

Still, he adds, “the downgrade is a reflection that there doesn’t seem to be a legitimate path to get the country’s debt figures back on track, or at least to stabilize them. And in the interim, any imbalance between supply and demand could cause rates to drift up — and that would impact the returns of fixed income investors.”

Sovereign debt has long troubled the U.S., but it can be a useful tool.

No less a personage than George Washington warned that no “pecuniary consideration is more urgent” than paying down public debt — which the fledgling republic had already incurred during the Revolutionary War.

That sentiment, which the president penned in a message to the House of Representatives in 1793, neatly encapsulates the duality of debt. It can be a painful albatross, but it can also help governments achieve important goals: For instance, the only other time U.S. debt-to-GDP ratio breached 100% was in the aftermath of World War II, when deficit spending was critical to the war effort.

Federal debt projected to top 120% of GDP in 10 years

Sources: Capital Group, Congressional Budget Office (CBO). GDP, or gross domestic product, is the total value of all finished goods and services produced or provided in a country or region during a specific time period. CBO projections as of March 2025.

Similarly, while much of today’s deficit spending is to keep the day-to-day apparatus of state operating, some of the biggest contributors to the modern debt total were similarly world-shaking catastrophes — the enormous shocks of the global financial crisis in 2008 and the COVID-19 pandemic of 2020, says Capital Group investment director Jayme Colosimo.

“Excluding those two events, the debt has been broadly flat since 2007,” she adds.

That doesn’t mean that the debt isn’t growing now. Today, it continues to expand because of structural deficits — that is, annual budgetary shortfalls — that are growing faster than federal tax revenue, which itself tends to move with the country’s GDP. This has been exacerbated by rising interest rates, which increase the cost of debt.

Just as important, U.S. fiscal policy has largely been paralyzed by gridlock. There’s just not much appetite to raise taxes and precious few areas to make meaningful cuts. When Moody’s stripped the U.S. of its triple-A rating, it explicitly called out this dynamic, saying that “successive U.S. administrations and Congress have failed to agree on measures to reverse the trend of large annual fiscal deficits and growing interest costs.” Perhaps unsurprisingly, S&P Global had a similar appraisal when it became the first bond-rating agency to ding U.S. credit in 2011.

“Nobody wants to pay higher taxes. Nobody wants their spending cut,” Spence says. “There are no easy fixes that won’t ultimately impact the economy and people individually.”

Looking forward can be tricky when it comes to U.S. debt.

Still, it’s difficult to make any kind of confident prediction on U.S. debt. That’s partly because the country’s in a unique position — its economic preeminence and the vaunted position of the dollar sharply limit the usefulness of comparisons to countries such as Greece, which famously stumbled under its debt load in the mid-2010s, or to Japan, which has cautiously charted a path forward even as its debt-to-GDP ratio nears 300%, Colosimo explains.

“The U.S. has a completely different level of flexibility in debt issuance and demand than other nations,” she says. “There are no real direct comparisons.”

And previous projections have shifted as situations have changed. Take, for example, a 2023 projection that the amount spent on debt servicing would overtake defense spending in 2028.

“It actually happened last year,” Spence says. “You get a sense of how quickly the numbers have been changing. It’s a pretty amazing thing, to spend more money servicing your debt than you do protecting the country.”

The good news is that the U.S. isn’t in an irreversible debt spiral. Demand for Treasuries remains high, partly because of the dollar’s enviable position as the global reserve currency, or an asset that’s viewed around the world as relatively safe and liquid. Additionally, economic factors could break in the federal government’s favor.

“Very small changes in growth, productivity and inflation assumptions could change the trajectory of U.S. debt,” Colosimo says. “If artificial intelligence provides the level of productivity gains some Capital Group analysts think it could, the U.S. has a better shot of growing out of this debt challenge.”

S&P 500 Index is a market capitalization-weighted index based on the results of approximately 500 widely held common stocks. This index is unmanaged, and its results include reinvested dividends and/or distributions but do not reflect the effect of sales charges, commissions, account fees, expenses or U.S. federal income taxes.

Bond ratings, which typically range from AAA/Aaa (highest) to D (lowest), are assigned by credit rating agencies such as Standard & Poor's, Moody's and/or Fitch, as an indication of an issuer's creditworthiness.

Related insights

-

-

Economic Indicators

-