International Equities

For much of the 2010s, Germany’s economy was the envy of its European peers. Celebrated for precision engineering, chemical giants and industry-leading autos, the country’s manufacturing prowess made it the economic heavyweight of Europe.

But in the last five years, Germany’s fortunes have taken a turn. The economy has stalled amid a stream of headwinds, both cyclical and structural. The war in Ukraine blunted its supply of cheap Russian gas. China morphed from customer to fierce competitor. And a worsening geopolitical environment means Germany now needs to raise defense spending while contending with U.S. tariffs.

Germany has struggled with issues common to much of the West, including tensions around immigration, an aging workforce and stalling globalization. Yet a fair number of challenges are self-inflicted. That includes restrictive fiscal policy, years of underinvestment in infrastructure and education, and a long-running failure to capitalize on the digital revolution.

Of course, Germany has successfully adapted to big shocks to its competitiveness before, such as in the 1980s with the rise of Japanese manufacturing and again in the 1990s and 2000s following German reunification and the rise of eastern Europe. The question is whether it will be able to do so again.

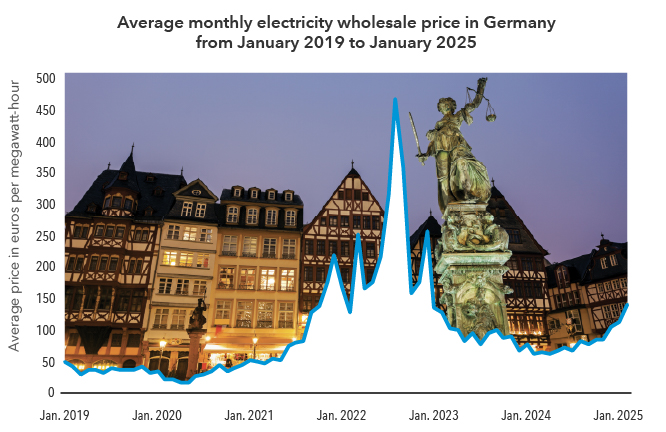

Germany's electricity prices have fallen from their pandemic peak

Source: Statista.

I believe Germany is well equipped to deal with the current challenges. It retains distinct advantages, including a skilled labor force, market-dominant positions across a number of industries and nimble midsize businesses that have a track record of pivoting quickly to seize new opportunities.

Besides, incoming Chancellor Friedrich Merz appears to grasp the challenges facing Germany and has overseen the largest shift in its fiscal policy stance in a generation. In March, Germany passed a package of measures that lifted previous constraints on defense spending and established a 500 billion-euro investment fund earmarked for upgrading infrastructure. This loosening in fiscal regime should help to smooth the industrial transition, support private investment and lift business confidence.

Germany has barely grown in five years.

The past five years have tested Germany’s economic model. Growth has stalled, energy costs have risen, the U.S. has imposed tariffs on its imports and its manufacturing dominance appears threatened.

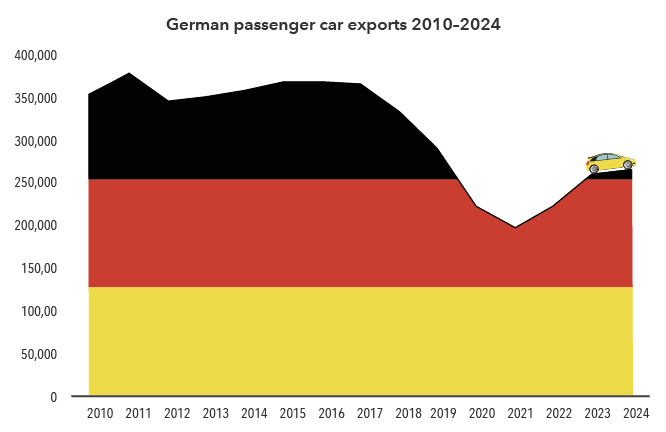

The pressure on Germany’s industrial base is perhaps most visible in the auto sector, long a pillar of the country’s economic strength. In recent years, Chinese carmakers have gained significant ground by producing high-quality electric vehicles (EVs) at very competitive prices. As a result, Chinese consumers are increasingly choosing domestic producers and Chinese automakers have rapidly expanded their presence in international markets, including in Europe. While German manufacturers still lead in the luxury and combustion-engine segments, China’s expansion into the mass-market EV space has put pressure on German and other European manufacturers.

Germany’s economic struggles are not entirely unexpected. A number of factors — including a cultural aversion to rising public debt, weak domestic demand and an approach to policy that can be described as “cautious incrementalism” — have stymied Germany’s ability to adapt to a changing global economy.

In addition, Germany is still recovering from the energy shock following the start of the war in Ukraine, which generated a sharp spike in gas prices beginning in 2022. Although prices have largely decreased, they remain higher than before the war.

Easing up on the debt brake is a good first step.

The malaise in Germany has prompted, for some, a reappraisal of former Chancellor Angela Merkel’s record. Her supporters credit her with overseeing an economy characterized by years of strong growth, political stability, low public debt and a welcoming policy toward asylum seekers. But critics fault her for mistakes in foreign and energy policy, as well as her strict commitment to a balanced budget that led to chronic underinvestment in infrastructure.

Germany's car exports have fallen in the past decade

Source: Statista.

Despite proclaiming a “Zeitenwende,” or historic turning point, Merkel’s successor, Olaf Scholz, struggled to manage his three-party coalition and was ousted in a no-confidence vote in December. Among other problems, he was unable to find agreement to raise the debt brake — the country’s constitutional limit on government borrowing — which severely constrained the government’s ability to stimulate the economy.

The debt brake, which was enshrined in Germany’s constitution in 2009, caps the deficit at 0.35% of GDP. Despite years of weak growth, the debt brake prevented lawmakers from pursuing the extent of fiscal stimulus undertaken in the U.S. and elsewhere.

That is why Merz’s swift action to materially loosen fiscal policy in Germany prompted such a large reaction in markets. Most investors had assumed he would also struggle to reach agreement, but in collaboration with two other parties, he won approval for a large package that includes increased defense outlays and an infrastructure fund to be spent over the next 12 years. This loosening of the debt brake is an essential step toward economic recovery and indicates a new willingness to break with the incrementalism of the past.

There are opportunities for Germany’s path forward.

Despite its challenges, Germany’s economic resilience is often underestimated. Its private sector remains a powerful force, especially the many small and mid-sized businesses that make up roughly half of Germany’s overall output. These firms are agile, have strong links globally and dominate in obscure industrial niches. While the car industry faces stiff challenges, other sectors — particularly green tech and pharma — appear to have solid prospects.

The new structure of the Bundestag, Germany's parliament, is also likely to support a shift to more pragmatic policy. Merz’s center-right party reached a deal to form a two-party coalition with the center-left Social Democrats. This partnership may find it easier to reach consensus than Scholz’s three-party coalition, which was often hamstrung.

Germany won’t bounce back overnight. But the early moves by Chancellor Merz mark a decisive break with the past and suggest a real and durable shift in thinking in Berlin. Loosening the debt brake, investing more at home and charting a more assertive economic course signal that Berlin understands the scale of the challenges it faces abroad and at home.

Germany’s economic model isn’t broken — it just needs updating. Germany’s shift to a more pragmatic approach to policy, particularly fiscal policy, can be seen as a recognition that more of its growth must be driven domestically in the coming years. After all, the post-pandemic experience in the U.S. demonstrates that looser fiscal policy can facilitate private sector investment and innovation. In a world that’s increasingly fragmented, Europe needs a strong and resilient Germany more than ever.

Related Insights

Related Insights

-

-

Global Equities

-

U.S. Equities

Beth Beckett

Beth Beckett