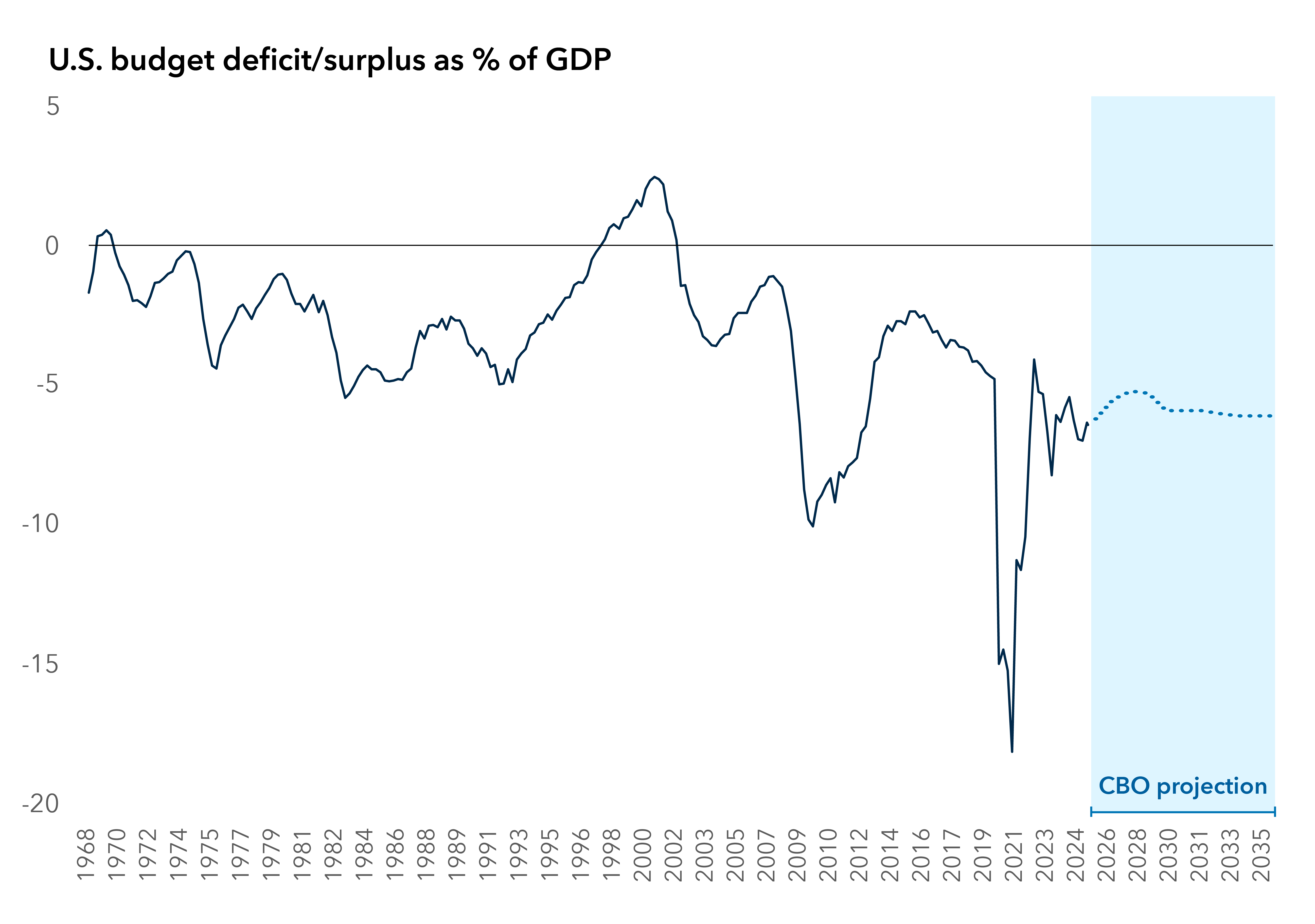

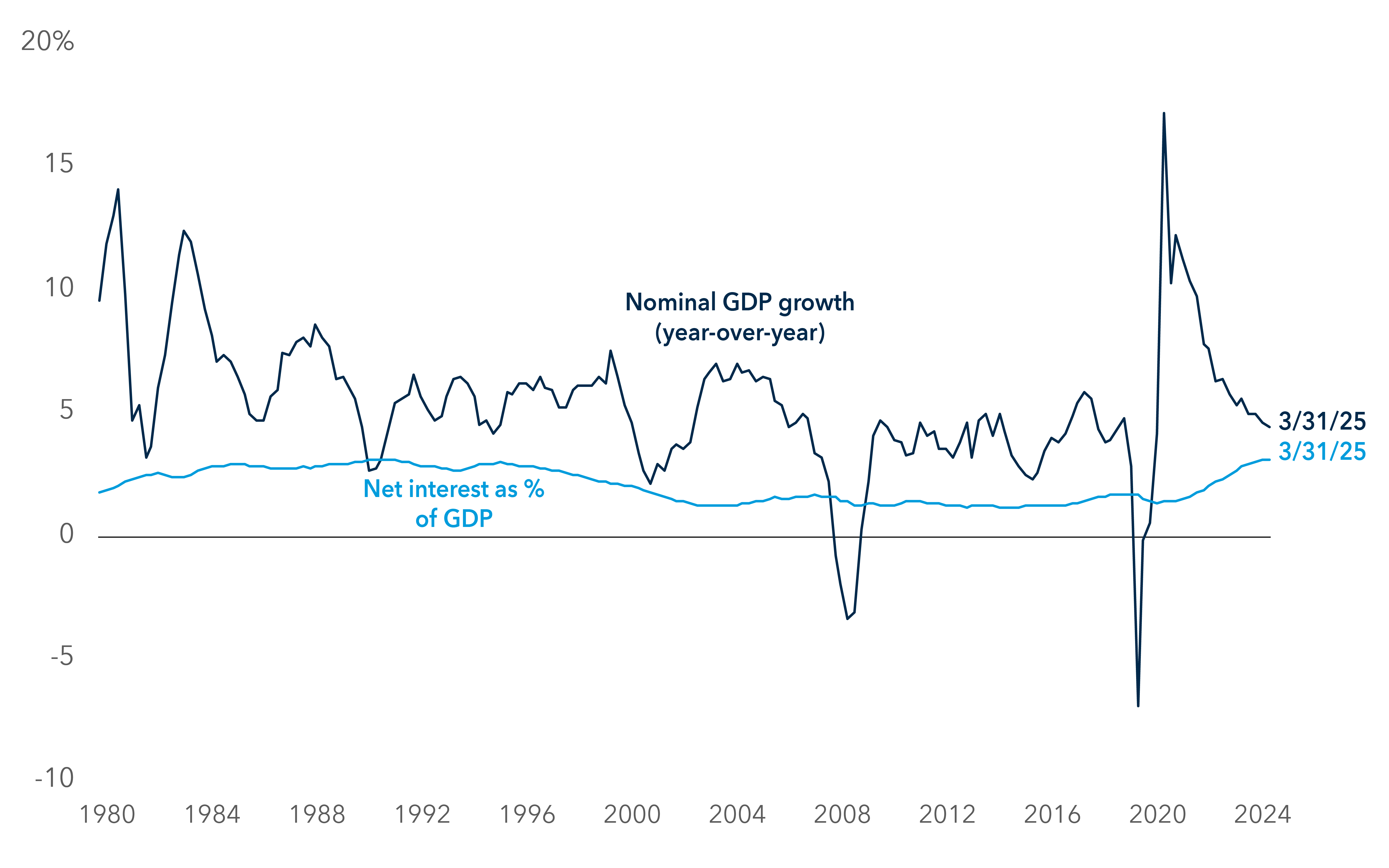

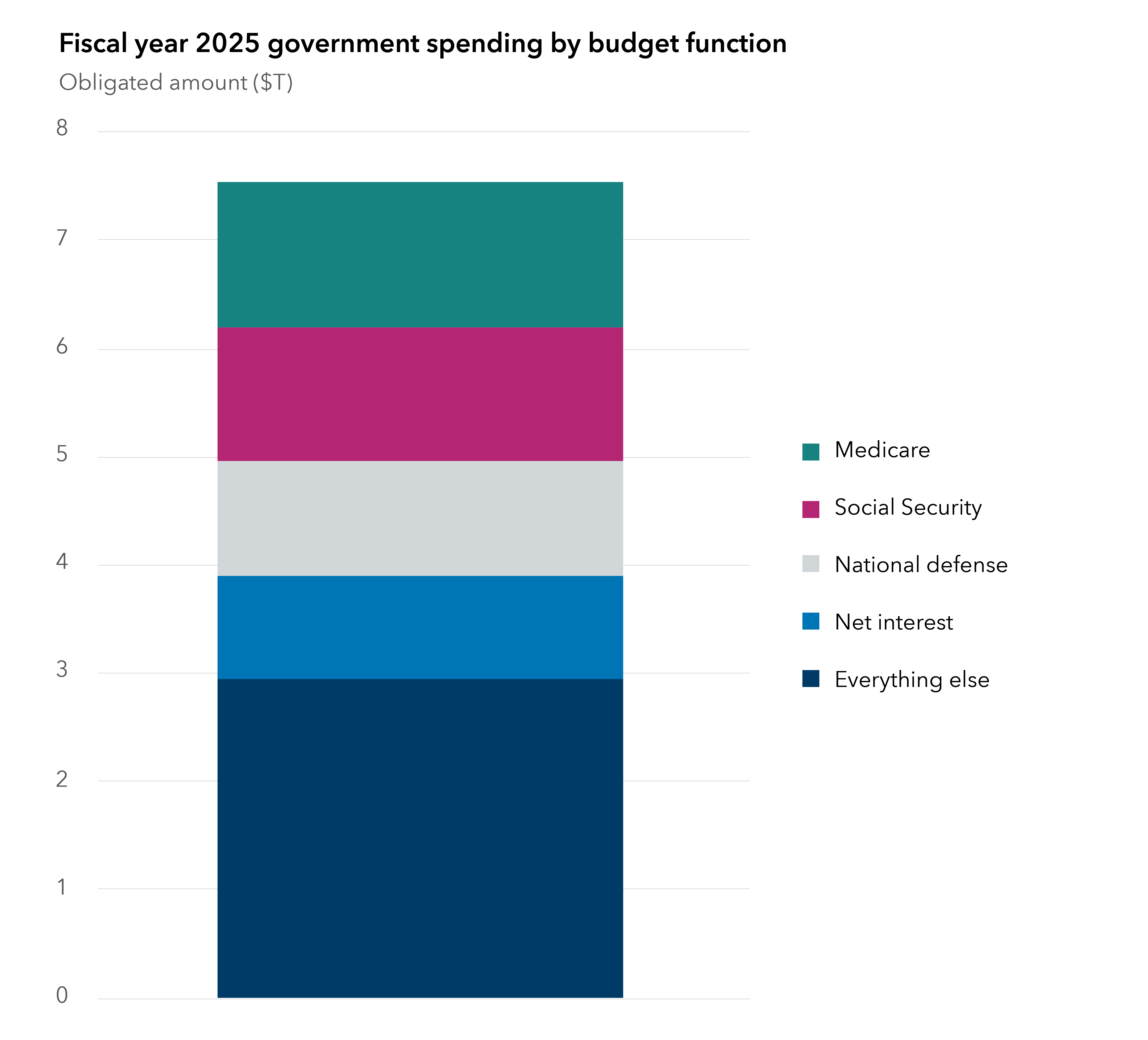

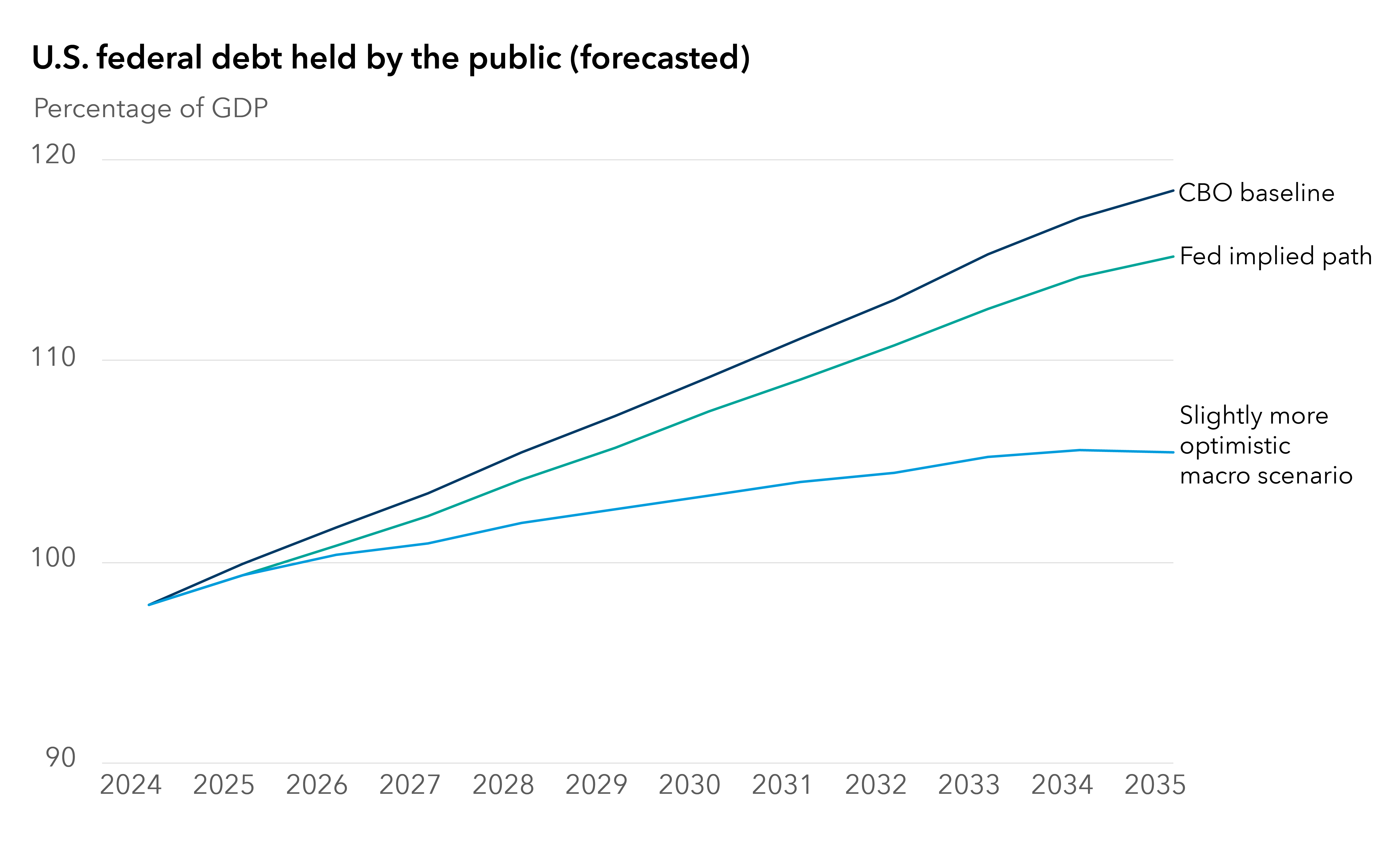

Is the U.S. national debt growing out of control? Predicting when or if a tipping point may be reached is difficult (or impossible), but the country faces growing fiscal challenges as its soaring interest burden is heightening concerns about long-term debt sustainability.

To be clear, there is no indication that a crisis is imminent. The federal government has operated with a deficit for much of its existence, and this has not resulted in significant challenges for either the bond market or the broader economy. That said, the increasingly perilous debt dynamics could eventually create problems without some sort of corrective measures. And it is prudent to examine the scenarios that could play out should we ever get to that point.